What is Local Law 97?

Skylight’s all-in-one explainer of New York City’s landmark building decarbonization law — and what it means for the city’s residential buildings.

View from the roof of Two Charlton Owners Corp. Photo: Hannah Berman

Unlike most places in the US, it’s not cars or factories that are primarily to blame for New York City’s greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions — it’s buildings. All of the office towers, storefronts, and residential buildings in our densely-populated city require heating and electricity, and the energy produced for those buildings accounts for more than two-thirds of the city’s emissions.

The lion’s share of those building emissions comes from big buildings, defined as those larger than 25,000 square feet. To address this, New York City has passed an ambitious piece of legislation known as Local Law 97 (LL97), which requires buildings to cut their carbon emissions. LL97 aims to reduce overall building emissions by 40 percent by 2030, which would in turn reduce the city’s overall GHG emissions by 10 percent; its ultimate goal is net-zero emissions city-wide by 2050. If implemented successfully, this law stands to have great impact on New York’s future, and can also serve as an example to other cities for how to tackle climate change.

The first GHG emission limits set by LL97 apply to approximately 34,000 buildings in 2025, and buildings that don’t meet the requirements will likely be fined. Stricter limits will be applied in 2030, and then gradually increase every four years until buildings meet the zero emissions goal of 2050. The law applies to residential and commercial buildings alike, but one of the bigger challenges for New Yorkers will be reducing emissions in the multifamily residential buildings where they live — which is where Skylight comes in.

Below is Skylight’s guide to navigating this complex and comprehensive law, with answers to common questions about LL97’s goals, requirements, and deadlines. As we continue to craft a roadmap for New Yorkers decarbonizing their buildings, consider this resource a starting point — the rules of the road for our city’s journey toward carbon neutrality.

Where did Local Law 97 come from?

LL97 was first passed by the City Council in 2019 as the main component of the Climate Mobilization Act (CMA), a legislation package aiming to reduce GHG emissions in the city and create new green energy jobs. Passing such an ambitious law didn’t come without political challenges: The interventions required by LL97 can be very expensive, and it has received significant pushback from the real estate lobby. While new proposals to limit its scope continue to be introduced, LL97 remains the law of the land in New York City.

What buildings does LL97 apply to?

LL97 applies to three groups of buildings:

- Individual buildings bigger than 25,000 square feet;

- Two or more buildings in the same tax lot bigger than 50,000 square feet combined; and

- Two or more condos managed by the same board that exceed 50,000 square feet combined.

Let’s break that down. A tax lot, which is identified by a unique number in city records, can contain one or more buildings. If the lot’s combined surface exceeds 50,000 square feet, all of the buildings on the lot have to comply with LL97 requirements. Still, every building must comply according to its own characteristics; for instance, if a lot comprises private housing as well as affordable housing and, say, a place of worship, each would need to adhere to the compliance pathway laid out for that specific type of building. (More on that later.)

There are exceptions for some buildings — for instance, utility producers or garden-style apartments. However, the square footage of the exempt buildings is still included in the calculation to determine whether the broader tax lot — and the other buildings on it — must comply with the law.

For instance, imagine that a 45,000-square-foot private apartment building and a 10,000-square-foot power plant sit on the same lot, and the total square footage is large enough that both buildings have to abide by LL97 requirements. This means that the power plant can demonstrate its eligibility for an exception (see below), while the apartment building must adopt the measures required by the law.

The Department of Buildings (DOB) compiled a preliminary list of the thousands of buildings covered by LL97. The list features covered tax lots, not individual buildings, so even though it provides information on compliance (for instance, when the requirements begin to apply), the specific details may vary for different buildings on the same lot. The list is non-exhaustive, non-binding, and subject to change, so the DOB recommends working with an engineer or an architect to confirm the status and requirements for a building.

What are the requirements for covered buildings?

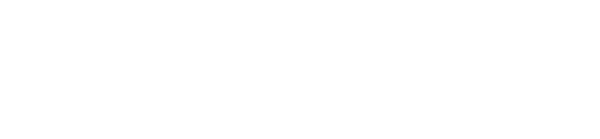

The vast majority of residential buildings covered by LL97 fall in one of two buckets regulated by two provisions in the law: Article 320 and Article 321. The law makes a distinction between buildings based on residents’ income as a proxy for their assumed capacity to pay for clean energy improvements.

Article 320 v. Article 321. Skylight

The first group, regulated by Article 320, comprises 34,000 private buildings, including those with some rent-regulated units. For these market-rate buildings, LL97 regulation has technically already begun, and those buildings must file their first GHG emissions report with the DOB by May 2025. Buildings with some rent-regulated units (but still no more than 35 percent) have to start working to meet the requirements in 2026, and file the first report in 2027, while Mitchell-Llama buildings and buildings with income-restricted units have until 2035 to meet emission limits, and must start filing annual reports in 2036.

Article 321 governs buildings where more than 35 percent of units are rent-regulated, income-regulated co-ops, and houses of worship. These buildings only have to file one compliance report, by May 2025, demonstrating either that their emissions are below the levels required in 2030, or that they have applied all of the energy conservation measures prescribed by Article 321. These measures include interventions such as temperature control for radiators, piping insulation, and upgraded lighting. The two articles also establish different penalties in case of noncompliance.

On top of these two groups, LL97 also regulates 5,500 city-owned buildings, which will have their own deadlines. City buildings will have to cut emissions by 40 percent compared to 2006 levels by 2025, and by 80 percent by 2030. New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA) buildings have less strict deadlines: They must cut emissions by 40 percent in 2030 and 80 percent by 2050, compared to their 2006 levels.

How are a building’s emissions calculated?

A building’s GHG emissions are a calculation of the amount of carbon and other greenhouse gases a building releases, depending on the energy it uses to operate — be it electricity, gas, or other fuel. LL97 assigns a “carbon coefficient” to each fuel to account for the different levels of emissions they create. The total emissions of a building are calculated by multiplying the amount of fuel a building uses each year by the appropriate coefficient, according to the fuel source.

For 2024 through 2029, the coefficients for common fuel types are as follows:

- Utility electricity — 0.000288962 tCO2e per kwh

- Natural gas — 0.00005311 tCO2e per kBtu*

- Fuel Oil #2 — 0.00007421 tCO2e per kBtu

- Fuel Oil #4 — 0.00007529 tCO2e per kBtu

- District steam — 0.00004493 tCO2e per kBtu

*kbtu= kilo-British thermal units

A building’s GHG emissions are calculated as:

Σ (Annual fuel use x Emissions coefficient of fuel type)

A building’s GHG emissions limit is the maximum amount of emissions a building is allowed to produce under LL97 — in other words, it’s an emissions cap, used to define and enforce fines. This emissions cap varies depending on a building’s size and property type, and it will gradually go down year after year as we approach the goal of zero emissions in 2050. The GHG emissions cap is calculated by multiplying a building’s total floor area by its Emissions Factor, or the intensity limit for carbon emissions for a given type of property, according to the EPA’s Energy Star program.

For 2024 through 2029, the emissions factor for multifamily housing is 0.00675 (tCO2e/sf). So a residential building’s GHG emissions limit is calculated as:

Building’s gross floor area x 0.00675 (tCO2e/sf)

A building is in compliance with LL97 when:

Annual GHG Emissions < GHG Emissions limit

When does Local Law 97 take effect?

Local Law 97 Compliance Timeline. Skylight

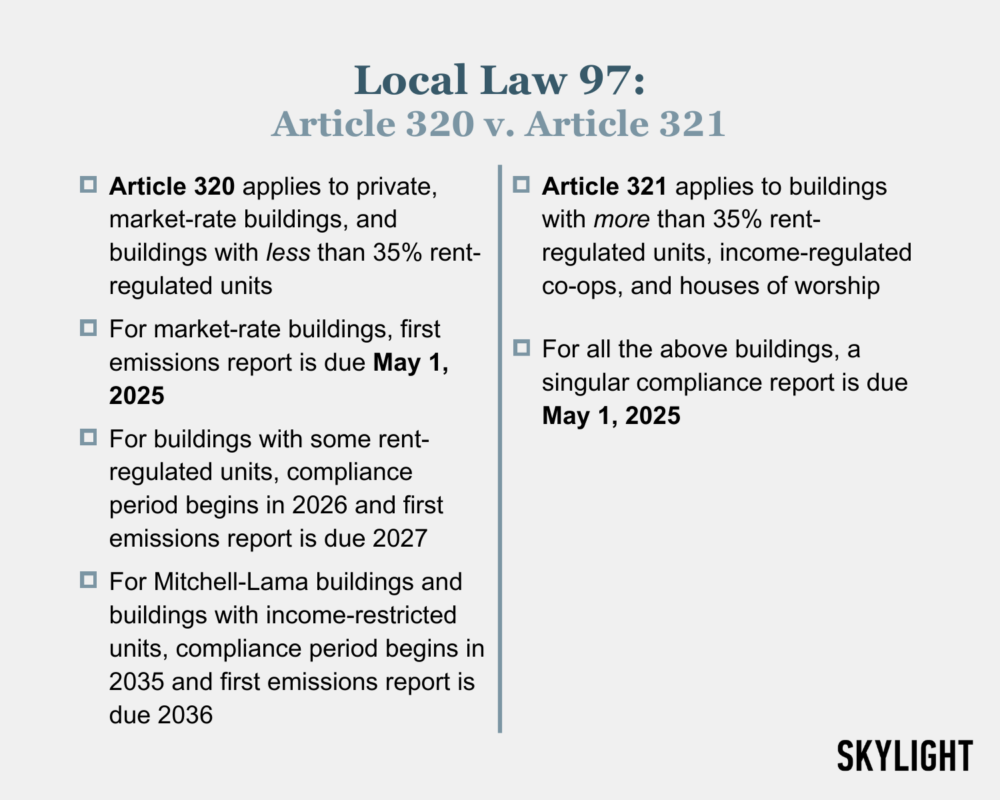

Past deadlines:

- LL97 was approved in 2019.

- Specific emissions caps were agreed upon in 2022.

- The compliance period started in January 2024, when buildings had to meet the emission caps assigned to them for the five years from 2024 to 2029.

- In December 2024, buildings regulated by Article 321 either had to demonstrate that they implemented the prescribed conservative measures, or that they were already meeting the requirements set for 2030.

As the law goes into full effect, these are the upcoming deadlines:

- May 2025: Buildings have to report their emissions for the previous year, which will show whether their caps were met or they have to pay fines. The 2025 report will be the first, and will be followed by yearly reports every May.

- June 2025: At the end of the fiscal year, city buildings have to demonstrate a 40 percent reduction in emissions, compared to their levels in 2006.

- January 2026: Buildings with 35 percent or fewer rent-regulated units have to begin complying with the emission limits.

- January 2030: Stricter emission limits, set for the years 2030 to 2034, come into effect. NYCHA buildings have to demonstrate cutting their emissions by 40 percent compared to 2005.

- January 2035: Mitchell-Llama buildings and buildings with income-restricted units have to begin complying with emissions limits.

- 2050: Citywide goal of net zero emissions; large buildings must cut emissions by 80%.

What are the Local Law 97 fines?

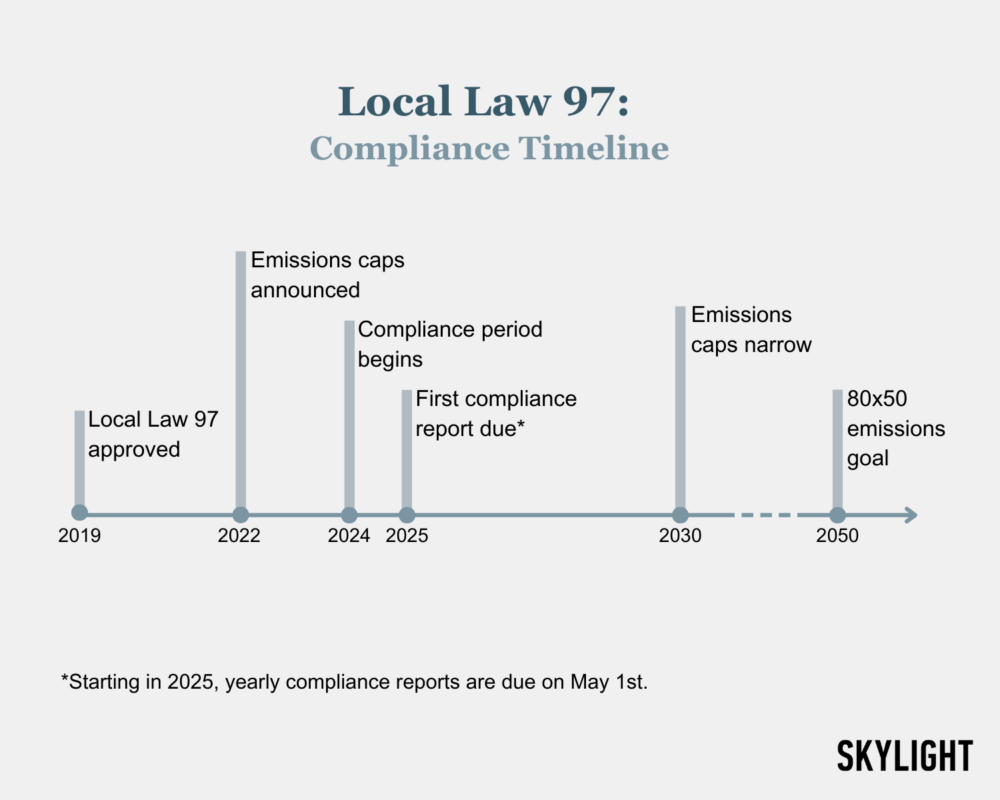

Articles 320 and 321 both detail the penalties applicable to the buildings that fail to submit a report or meet the GHG limits.

For buildings subject to Article 320, failing to submit a report on time leads to a monthly fine of $0.50 per square foot of the building. Reports are due on May 1 of each year, but there is a “grace period” between May 1 and June 30. After June 30, this penalty of $0.50 per square foot per month kicks in. (In some limited circumstances, there may be opportunities to file for an extension beyond the grace period, for a fee.)

If a building’s emissions are determined to exceed the limits, the building pays a fine of $268 per ton of excess CO2 emission.

For buildings subject to Article 321, both failing to submit a report and to comply with emissions regulations lead to a flat penalty of $10,000 each.

Local Law 97 Fines. Skylight

So, for a market-rate, 113,000-square-foot apartment building under Article 320, failing to submit a report on time leads to a penalty of $56,500 per month until the report is filed. If that building submits a report showing that it emits 450 tons of carbon annually, but has an emissions limit of 350 tons, it’s subject to a penalty of $26,800 — $268 times the 100 tons of CO2 in excess.

How can a building get started with decarbonization?

It takes many different types of fuels to power a big building. Heating, air conditioning, hot water, and lighting all require electricity, gas, or oil as fuel, and all those energy sources produce carbon emissions. Accordingly, each building will require its own strategies to reduce emissions from all those different energy sources. There is no one-size-fits-all intervention for buildings covered by LL97 and looking to cut their emissions, and not every building will need to do a complete overhaul of its energy systems in order to comply.

LL97 does not mandate the adoption of any specific retrofits. The choice is at the owner’s discretion, and any combination sufficient to reduce GHG emissions to the required levels is permissible. For instance, the International Tailoring Company Building, a pre-war co-op, updated its heating and cooling systems to meet LL97 emissions limits, while for another decades-old building in Manhattan, the first intervention was recladding the exterior to improve energy efficiency.

Some retrofit projects apply to the building envelope — for example, upgrading windows and doors, and sealing any leaks to improve insulation. Others focus on lighting, such as using LEDs or sensors that turn lights off in common areas if no one is there. Still others optimize hot water by installing better heaters and improving distribution systems. Further, buildings can opt to install more comprehensive renewable energy systems, such as replacing a gas boiler with heat pumps, which vastly reduce GHG emissions.

Fuel-burning boilers are often the first big thing to go when apartment buildings decarbonize. Photo: Hannah Berman

What are Local Law 97 offsets and RECs? How do they work?

NYC Accelerator, a City program that helps buildings reduce GHG emissions, also offers building owners a variety of resources to help guide their retrofit process, including information on specific technologies like solar and insulation, contacts for service providers to help execute projects, and a list of state and national incentives to save money on projects. It also has an online resource to help buildings check their compliance status, as well as what fines they may expect to receive and when.

Buildings that have demonstrably begun GHG reduction interventions but haven’t yet met the requirements can receive a fine reduction through a so-called “good faith” pathway to compliance.

LL97-covered buildings facing fines have the option to reduce them by buying carbon offsets and/or Renewable Energy Credits (RECs).

Carbon offsets are offered as a way to “make up for” an individual building’s emissions by investing in other decarbonization efforts in the city. The only carbon offset currently eligible for LL97 compliance is the New York City Affordable Housing Reinvestment Fund (AHRF). This program, administered by NYCEEC, uses money from offset purchases to fund retrofit projects at qualifying buildings designated as affordable housing. LL97-covered buildings can buy offsets to cover only up to 10 percent of their total GHG emissions. The offsets aren’t particularly beneficial from a financial standpoint, as they cost exactly the same amount as the fines — $268 per ton of CO2 — but buildings that purchase them maintain eligibility for financing, which can act as an incentive.

Although some observers have praised the offsets program for directing earnings toward affordable housing, others have criticized the program, as they claim it encourages building owners to buy their way out of penalties rather than make the kind of interventions that are required to cut emissions.

Buildings may also meet their LL97 emissions limits by buying certain local types of Renewable Energy Credits (RECs). These credits, which are issued by the state, fund the delivery of clean, renewable energy to New York’s electricity grid. Each REC corresponds to one megawatt-hour of renewable energy delivered to the grid, and prices are set through NYSERDA, a statewide entity. However, LL97 stipulates that RECs purchased must apply to renewable energy projects that affect New York City specifically, not just any project in the state of New York. There are currently few existing projects that fit that bill. However, a 2022 NYSERDA initiative to increase renewable energy sources for New York City intends to bring more eligible projects online in the coming years.

Are there any exemptions to Local Law 97?

The breadth and complexity of LL97 also mean that there are quite a few caveats and exceptions. For instance, buildings with special circumstances such as high-density occupancy or housing operations critical to human health and safety have higher GHG limits, as do not-for-profit hospitals and healthcare facilities.

Individual buildings can challenge their inclusion in LL97, ask for adjustments in their GHG limits, and request more information via email at ghgemissions@buildings.nyc.gov.

What’s next for Local Law 97?

The political push to weaken LL97 hasn’t ended with its implementation. Perhaps the most significant challenge currently standing, known as Intro 772, is a bill sponsored by about half the City Council that was introduced in April 2024.

If passed, Intro 772 would dramatically reduce the impact of LL97 in two ways: First, it would increase building carbon limits, by allowing residential buildings to include any ground floor open and green space in the surface calculation, hence increasing allowed emission; second, it would suspend penalties for a decade, and reduce penalties until 2045. Some buildings also qualify for tax cuts, such as the ones established by J‑51. This bill, signed into law in December 2024, allows affordable buildings to get tax cuts for investments made to capital improvements, such as the ones required by LL97.

In order to avoid fines, many buildings have already begun taking actions such as retrofitting equipment to promote energy efficiency or improving maintenance practices to be less wasteful. Large city buildings have reported a reduction in GHG emissions for the past five years, and as of 2024, 92 percent of all buildings covered by LL97 met the requirements set by the law.

Local Law 97 FAQs

When does Local Law 97 come into effect?

The compliance period for LL97 started in January 2024. Current emissions caps are in place for five years, from 2024 to 2029, before becoming stricter in 2030.

How do I know if my building is subject to Local Law 97?

LL97 applies to buildings above a certain size based on the square footage of a building or tax lot. New York City government maintains a preliminary Covered Buildings List (CBL) that property owners can search by address, tax lot number, or unique building number. A PDF version of the Covered Buildings List can be found here.

When is the first compliance report due?

The first buildings subject to compliance must file reports by May 1, 2025, and then by the same date every year after. There is a grace period from May 1 to June 30. (Update, June 30: The NYC DOB announced that for 2025, buildings needing more time to file their reports can apply for an extended reporting deadline of December 31. But requests for an extension must be submitted by August 29.)

What resources are there to begin checking compliance?

NYC Accelerator, a program that helps buildings reduce GHG emissions, created an online resource to help buildings check their compliance status, as well as what fines they may expect to receive and when.

Additionally, Building Energy Exchange, in partnership with NYC Accelerator, has developed a Carbon Emissions Calculator to estimate a property’s carbon emissions and expected penalty. Users can search for a property by address or input building information manually to get an estimate of how its carbon usage measures up against the limits for different enforcement periods between 2025 and 2050. However, the creators of the calculator emphasize that it is only meant to be used as an estimating tool, not as a definitive calculation for use on a building’s emissions report.

How do buildings avoid Local Law 97 fines?

For all buildings taking the traditional pathway, the only way to avoid fines begins with filing compliance reports on time, with the help of a registered design professional. Stay tuned for Skylight’s forthcoming article explaining the process for filing compliance reports.

Some buildings can plan to reduce their fines by buying carbon offsets and some local types of Renewable Energy Credits (RECs). However, carbon offsets are capped — buildings can only use them to offset up to 10 percent of their GHG emissions — and they cost the same amount as the fines. Other buildings with special circumstances might request exemptions in order to avoid fines.

Correction (Aug. 7, 2025): This article was updated to accurately reflect rules around measures that can be taken to counteract emissions and avoid LL97 fines. A previous version of this article incorrectly conflated carbon offsets and Renewable Energy Credits (RECs).